Writs of Eviction in Virginia

In 2023, Virginia passed legislation (HB 1836, SB 1089) that requires a sheriff executing a writ of eviction to return the executed writ to the issuing court to be recorded. The law went into effect on July 1, 2023 and the Office of the Executive Secretary of the Supreme Court of Virginia will report on the number of executed writs during each fiscal year. In anticipation of this measure – the number of executed eviction writs – becoming a key metric of eviction in Virginia, we evaluate the place of executed writs in understanding the scale of the involuntary loss of housing that occurs in the larger picture of eviction. Sheriff-executed writs capture only a small slice of evicted households.

Writs in the Formal Eviction Process

The most common way people lose their rental housing through eviction is not by a Sheriff-executed court order, called a writ of possession in Virginia. Instead, most displacement occurs through informal eviction: “landlord-initiated involuntary relocations that occur beyond the purview of the court”.1 Surveys of renters in other cities have found that nearly half of all forced moves by renters are “informal evictions”, meaning renters were forced to move outside of a formal court removal process. In fact, formal eviction via courts comprised only 24% of all forced moves.2 The ratio of informal-to-formal evictions for the United States is estimated to be from 5.5 to 2 informal evictions for every formal eviction. That is, for every household displaced through a formal court eviction, between two and six additional households are forced to move in response to warnings or threats from their landlord.3 Focusing only on formal court evictions misses a substantial number of forced moves.

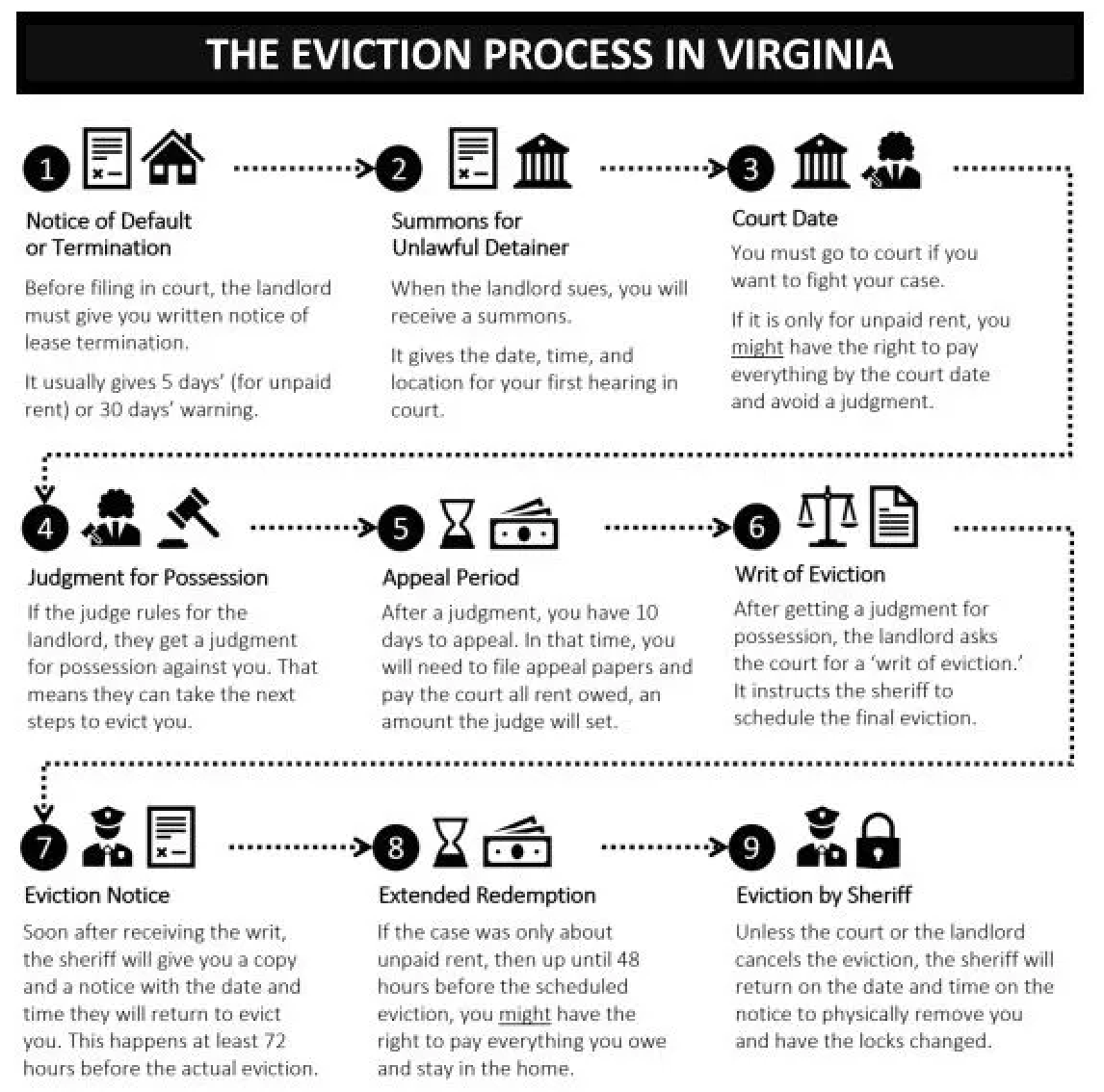

Formal evictions occur through the court system and must follow a standardized procedure. According to the Virginia Poverty Law Center the eviction process consists of nine steps, depicted below. At each step in the process the tenant and landlord may reach resolution or the tenant may move out, ending the formal eviction process. Even within a formal eviction process, then, the number of eviction judgments or the number of executed writs underestimate the true frequency of evictions. For instance, a tenant may choose to move when they first receive a notice of default or once a judge has provided a judgment for possession to the landlord. In neither case would the data reflect that a sheriff performed an eviction. Unfortunately, there is no single piece of data that tells us about all the times when renters are displaced. And neither eviction judgments nor executed writs provide a full accounting of all of the instances in which a household moves in response to a process that begins with a court filing.

The Flow of Evictions through Virginia Courts

Using newly available data on executed writs in Virginia, provided by the Civil Court Data Initiative at Legal Services Corporation, we examine the number of executed writs relative to the number of eviction judgments.4

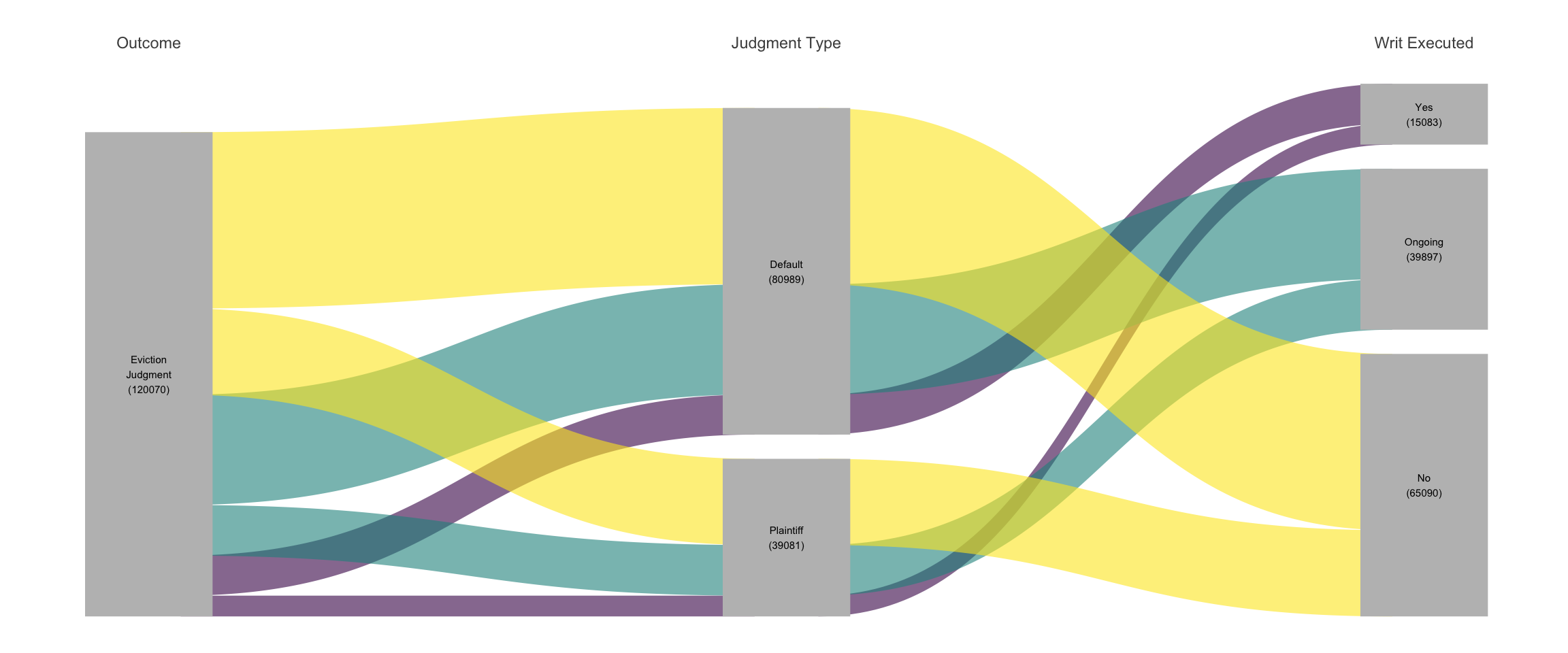

Below we show the flow of eviction cases that result in a judgment of eviction through each subsequent outcome: type of judgment and whether a writ is executed. While a writ is issued in about 60% of cases that ended with an eviction judgment, the writ was recorded as being executed only 20% of the time. Overall, only 13% of court-ordered evictions in Virginia end with the execution of an eviction writ.

There are 15,083 recorded instances of an executed writ. These are not the only evictions that occurred during this period. All 120,070 of these eviction cases represented here involved a judgment in favor of the plaintiff; most of them are likely to have ended with a household forced to move in response to a court process. But only 13% of them involved the intervention of a Sheriffs’ office.5

Regional Eviction Rates in Virginia

Eviction outcomes as processed through the court system vary across the state. Below we use the Legal Aid Service Areas of Virginia to summarize elements of this variation, including:

- The rate of eviction cases filed as a percent of renting households (Eviction Filing Rates);

- The frequency of court-ruled evictions as a percent of renting households (Eviciton Judgment Rates);

- The likelihood that plaintiffs request a writ of eviction after winning an eviction case (Writ Issuance Rates);

- The rate at which writs are executed once they have been issued (Writ Execution Rates).

The overall rate of eviction judgments is especially high in localities served by the Legal Aid Society of Eastern Virginia (particularly Williamsburg, Portsmouth, Hampton, and Newport News) and by the Central Virginia Legal Aid Society (particularly Petersburg, Chesterfield County, Hopewell, Colonial Heights, Richmond, and Henrico County).

The overall rate of eviction judgments is especially high in localities served by the Legal Aid Society of Eastern Virginia and by the Central Virginia Legal Aid Society. Mirroring the eviction filing rates, eviction judgment rates are highest in the cities of Williamsburg and Petersburg with a 39% eviction judgment rate; followed by the cities of Portsmouth, Hampton, and Newport News (25% to 27%); with Hopewell city, Chesterfield County, Richmond city, Colonial Heights city, and Henrico County experiencing an eviction judgment rate of about 20%.

Writs of possession are issued most often in the region served by the Legal Aid Services of Northern Virginia, though the eviction filing rate and judgment rate are relatively low in this region.

Writs are recorded as executed at the highest rate in the Blue Ridge Legal Services area, though this area has the lowest rate of eviction judgments overall. The region contained in the Central Virginia Legal Aid Services area has the lowest rate of executed writs recorded in the case information, especially in conjunction with the high rate of eviction judgments.

To view these values by Virginia court jurisdictions – the number and rates of eviction filings, eviction judgments, writs issued, and writs executed – visit the locality-level table.

Eviction Writs and Evictions

The estimates by both legal aid service area and court jurisdiction highlight several peculiarities. In particular, multiple localities have a high number of eviction judgments accompanied by very few, or zero, executed writs recorded in the case information in the first year for which the new law has been in effect. Forty localities have no executed writs reported, including Richmond city, Henrico County, Chesterfield County, and several other localities with some of the largest number of eviction judgments. In all of these jurisdictions, writs were issued following 50% to 80% of the eviction judgments.

In addition, the number of executed eviction writs observed in this analysis is notably lower than the count reported by the Office of the Executive Secretary for the Virginia Courts (OES). Overall, the online court data reported here includes records of 15,083 executed writs between March 2023 and October 2024. Restricting the number to only those that occurred between July 1, 2023 through June 30, 2024, to align with the time period of the OES report, there are 11,457 executed writs. The OES reports that 22,177 writs of eviction were returned to the court for the same period.

Given the high number of jurisdictions reporting no executed writs, despite the high number of eviction judgments and writs issued, along with the more than 10,000 fewer executed writs we observe in the court database compared to the count by OES, we believe the data as represented in the Virginia court’s online case information system is incomplete. This appears inconsistent with the intent of § 8.01-471 of the Code of Virginia as amended by SB 1089/HB 1836.

When enacted, SB 1089/HB 1836 was touted as providing data to clarify the scope of the eviction crisis, providing new information on when and where evictions occur.6 But eviction writs capture only a small fraction of displacement due to eviction in the Commonwealth. And court evictions are only a portion of renter displacement. Even with full reporting of sheriff-executed writs of possession, the number of executed writs of eviction alone cannot provide an accurate representation of evictions in Virginia.

Why Estimating Eviction Matters

Whether forced to move by a Sheriff, an eviction notice, or because of an unanticipated rent increase, an involuntary move creates significant and lasting burdens for affected households, and casts a much wider net of harm for neighborhoods, local governments, and the broader public.7 Each eviction case that does go through the courts affects more than one person. While the typical eviction case only lists a single defendant, renter households have a median of 2.4 members. This frequently includes at least one child under 18; the presence of children in a household is associated with heightened eviction risk. In short, limitations in the data available to estimate eviction means research systematically underestimates the number of people threatened with court-ordered evictions in a given year.8

The effects of involuntary displacement are wide ranging and serious. For example,

Health

- In the first two years after receiving an eviction order the likelihood of homelessness and hospital visits increases.9

- Renters that experience eviction have been found to exhibit increased symptoms of depression and decreased health as eviction leads to increased exposure and vulnerability to diseases.10

- Experiencing eviction also leads to indulging in unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking and eating unhealthy food, higher rates of anxiety, psychological distress and alcohol dependence.11

- Evicted persons have a higher suicide mortality rate than non-evicted individuals.12

- Measures of eviction cases filed and judgments entered against a tenant for rent due, whether or not they ultimately result in a tenant’s removal, are all associated with increased rates of death;13 excess mortality in response to eviction filings was amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic.14

Financial stability

Child well-being

- Evictions have been linked to increased likelihood of maternal depression as well as increased incidences of adverse birth outcomes, such as low birth weight, premature birth and infant mortality.17

- A 5 year study found that both formal and informal evictions lead to increased odds of younger children’s developmental risk and admission to hospitals from the emergency department, due to acute health concerns that require inpatient care and poor health in children.

- Informal evictions have been found to lead to loss of social connections due to having to transfer schools and loss of support systems.18

- Eviction has been linked to increased childhood hospitalizations and worse educational outcomes.19

The range of compounding harm following evictions underscores the importance of using multiple measures and approaches to better understand, and prevent, eviction and to describe the wider landscape of forced displacement. Formal evictions that occur through the court process – after a ruling or an executed writ – underestimate the number of evictions, and the number of adults and children impacted.

Contributions

This work is a collaboration between The Equity Center at the University of Virginia, RVA Eviction Lab at the Virginia Commonwealth University, and the Civil Court Data Initiative at Legal Services Corporation. The analysis was conducted by Michele Claibourn (UVA), Ben Teresa (VCU), and Logan Pratico (LSC) with additional research support from Henry DeMarco (UVA), James Lambert (VCU), Samantha Toet (UVA), and Corey Nolan (VCU).

Suggested citation: The Equity Center, RVA Eviction Lab, and Civil Court Data Initiative. January 2025. “Writs of Eviction in Virginia.”UVA Karsh Institute of Democracy Center for the Redress of Inequity Through Community-Engaged Scholarship, RVA Eviction Lab in the Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs at VCU, Civil Court Data Initiative at LSC. https://virginiaequitycenter.github.io/va-evictions/writs/writs_of_eviction.html

Footnotes

Matthew Desmond, Carl Gershenson, and Barbara Kiviat. 2015. “Forced Relocation and Residential Instability among Urban Renters.” Social Service Review 89(2): 227-262.↩︎

Matthew Desmond and Tracey Shollenberger. 2015. “Forced displacement from rental housing: Prevalence and neighborhood consequences.” Demography 52: 1751-1772.↩︎

Ashley Gromis and Matthew Desmond. 2021. “Estimating the Prevalence of Eviction in the United States: New Data from the 2017 American Housing Survey.” Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research 23(2): 279-289.↩︎

The data include all eviction cases filed from January 2023 through September 2024 that resulted in an eviction judgment.↩︎

Cases that end in dismissal or non-suit often involve a family moving as well, even though a writ will never be issued or executed in such cases. In addition to the 120,000+ cases that ended with an eviction judgment during this period, there were an additional 120,000+ unlawful detainer cases filed – the majority of these cases ended with dismissed or non-suit.↩︎

See, for example, [“Virginia begins collecting data on where evictions occur and when.”(https://virginiamercury.com/briefs/virginia-begins-collecting-data-on-where-evictions-occur-and-when/) Virginia Mercury, August 22, 2023.↩︎

Mindy Fullilove. 2016. * Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, And What We Can Do About It.* New Village Press.↩︎

Nick Graetz, Carl Gershenson, Peter Hepburn, Sonya R. Porter, Danielle H. Sandler and Matthew Desmond. 2023. “A comprehensive demographic profile of the US evicted population.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 120(41).↩︎

Robert Collinson, John Eric Humphries, Nicholas Mader, Davin Reed, Daniel Tannenbaum and Winnie van Dijk. 2024. “Eviction and Poverty in American Cities.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 139(1): 57–120.↩︎

Morgan K. Hoke and Courtney E. Boen. 2021. “The health impacts of eviction: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health.” Social Science & Medicine 273.↩︎

Hugo Vásquez-Vera, Laia Palència, Ingrid Young, Calos Mena, Jaime Neira, and Carme Borrell. 2017. “The threat of home eviction and its effects on health through the equity lens: A systematic review.” Social Science & Medicine 175.↩︎

Gracie Himmelstein and Matthew Desmond. 2021. “Association of Eviction with Adverse Birth Outcomes among Women in Georgia, 2000 to 2016.” Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey 76(11): 659-660.↩︎

Nick Graetz, Carl Gershenson, Sonya R. Porter, Danielle H. Sandler, Emily Lemmerman and Matthew Desmond. 2024. “The impacts of rent burden and eviction on mortality in the United States, 2000–2019.” Social Science & Medicine 340.↩︎

Nick Graetz, Peter Hepburn, Carl Gershenson, Sonya R. Porter, Danielle H. Sandler, Emily Lemmerman and Matthew Desmond. 2024. “Examining Excess Mortality Associated With the COVID-19 Pandemic for Renters Threatened With Eviction.” JAMA 331(7): 592.600.↩︎

Matthew Desmond and Rachel Kimbro. 2015. “Eviction’s Fallout: Housing, Hardship, and Health.” Social Forces 94. See also Collinson et al., 2024.↩︎

Himmelstein and Desmond, 2021↩︎

Diana B. Cutts, Stephaie Ettinger de Cuba, Allison Bovell-Ammon, Chevaughn Wellington, Sharon M. Coleman, Deborah A. Frank, Maureen M. Black, Eduardo Ochoa, Mariana Chilton, Felie Lê-Scherban, Timothy Heeren, Lindsey J. Rateau and Megan Sandel. 2022. “Eviction and Household Health and Hardships in Families With Very Young Children.” Pediatrics 150(4). See also Himmelstein and Desmond, 2021.↩︎

Cutts et al., 2022↩︎

Himmelstein and Desmond, 2021↩︎